Blog Archives

Post navigation

Changing Hazards Prompt Insurers to Rethink the Location of Risk

To ensure their risk assessment reflects risks on the ground, insurers and reinsurers are increasingly relying on location-based risk analysis.

Recent headlines about climate change make it difficult to bury one’s head in the (rapidly receding) sand.

In 2018, a total of nearly 400 natural disasters caused US$225 billion in damage worldwide. The insurance industry covered $90 billion of those losses, according to reinsurer Aon. For historical context, consider data from the Brussels-based Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters: In the last half century, the number of natural disasters worldwide has risen more than 450 percent.

Concern over the financial effects of weather events has rippled through other industries, including financial services. In a post titled “Hedging Climate News” on the Harvard Law School website, several finance professors outline a strategy for hedging against climate-based risk.

Viewed over a longer horizon, the numbers are staggering. Total global economic losses from natural disasters between 2005 and 2015 were more than $1.3 trillion, with direct losses in the range of $2.5 trillion since 2000.

The insurance industry is evolving from generalizations about location-based risk to sophisticated risk scoring based on GIS-powered location intelligence.

While scientists work to assess the fate of the planet, insurance companies are dealing with the immediate and long-term consequences and costs of climate change. Increasingly, insurers of all types are using location intelligence to get a more complete picture of risk at each property, across supply chains, and across portfolios.

The reality for insurers is that understanding risks specific to location matters greatly, and is key to reliable risk assessment and pricing models. Without accounting for the context of location, insurance companies put themselves at risk. And as the insurers of last resort, reinsurers face even greater exposure. They are the final entity in the chain of climate-change-related liability; the buck stops with them.

More Transparent Risk Analysis

Andreas Siebert, head of geospatial solutions at global reinsurer Munich Re, says the realities of climate change are making Munich Re’s underwriters hungrier for data that can provide both a holistic and fine-grained picture of climate-related property risks.

“We try to keep our clients insurable in the future by supporting them with not only the financial strength of Munich Re but also our knowledge and experience,” Siebert says.

Like other insurers, Munich Re needs highly granular data upon which to base its risk pricing, as well as greater transparency into how risk-related decisions are made throughout client supply chains. Increasingly, that means relying on location intelligence powered by a geographic information system (GIS), which maps, analyses, and models risk for a property and its surrounding area.

“More transparency means a better understanding of what the industry is insuring these days,” Siebert explains. “We have to learn more [about building] construction types, occupancies, the age of buildings—a lot of additional data. We have to bring it together to have the full transparency when we are doing risk assessment.”

For Munich Re, there is a tight linkage between business intelligence and location intelligence. “We are on our way to fully integrating both worlds,” Siebert says. “For us, it means we have direct access to the operational data, which we enrich and analyse with the capabilities of geo-analytics and other dashboard methodologies.”

Munich Re is bringing easy-to-use tools with geospatial capabilities to its underwriting practices. Since the underwriters are not geospatial experts, the tool has to be especially user-friendly and accessible.

Seeing Risk with More Precision

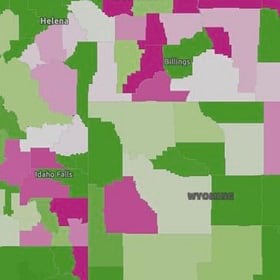

Until roughly the 1980s, the insurance industry did not think at a detailed level about the link between risk and location. That has changed dramatically. NatCat models, for instance, now compensate for the fact that areas that weren’t prone to wildfires are now hot zones.

With GIS-driven location intelligence, the risk profile is much more granular, examining questions such as, “How has this home in this neighbourhood been affected by wildfires and other risks?” Smart maps provide an immediate and compelling illustration of that risk.

Such location intelligence helps drive “point-based risk scoring,” which gives underwriters a more complete view of a property than they have traditionally had. Insurers might take into account everything from local soil composition to the types of trees in a nearby forest (since some are more fire-resistant than others), as well as age and type of property (and a long list of other factors) to arrive at a point-based risk score.

Location intelligence helps unify disparate data relating to a property and its type of risk, whether that is flood, hurricane, wildfire, hail, tornado, earthquake or other calamities. A holistic risk profile also includes threats such as terrorism and civil unrest. In fact, a small cohort of specialists—companies such as CONIAS Risk Intelligence—supplies multinational corporations with GIS-driven insight on where those risks exist, and to what degree.

The location intelligence these analysts deliver can affect multimillion-dollar decisions on how a supply chain is organised and which markets a company serves.

AI-Based Risk Scoring

Using GIS-based location intelligence, insurers have identified risks that appear counterintuitive, but actually reveal new realities. Case in point: Many Californians are not required to have flood insurance because most homes there are not in 100-year floodplains. However, one of the greatest risks in the last five years in California is flooding.

This seems strange for a state that has been in a drought for eight years. Yet, an analysis of location-specific factors reveals the culprits: soil composition, the amount of concrete, the lack of drainage, aging infrastructure, and the type of rainfall events increasingly common to California. In short, there’s more pooling of water and more flooding because the water has nowhere to go.

Location intelligence provides insurers a more nuanced and fully faceted picture of risk, rather than a simple “yes” or “no” answer to the question, “Is this property in a floodplain?”

GIS can quickly analyse those events and produce a risk score for a specific property or a dashboard reading of green, yellow, or red. According to Siebert and others in the industry, the process of data correlation and scoring is becoming automated through artificial intelligence (AI)—specifically machine learning (ML), which is trained to see patterns in large volumes of data. Going forward, all an underwriter will need to do is input an address, look at the score, and then only review a policy if it is automatically denied or flagged for more review.

Munich Re is doing location-based risk analysis, both internally and as a service for clients. For example, its NATHAN service—the Natural Hazard Assessment Network—helps companies assess the risks of natural hazards around the world, from location-based individual risk through to entire portfolios of assets.

“We combine data on global natural catastrophes and enable the user to upload their [property] portfolio to have a very complex and flexible location-based analysis,” Siebert says. Even professionals who don’t work with GIS—including claims managers and underwriters—can input an address and understand its risks, Siebert explains.

A Wealth of Imagery

In the insurance industries and across the business landscape, torrents of location-specific data are pouring in from new sources, including satellite images and aerial photography. Munich Re uses some of this imagery to better monitor storms and evaluate other extreme-weather events. The high-resolution images now assist claims adjusters and engineers in calculating losses on a per-building level.

This is another instance where location intelligence and business intelligence merge.

“We are working in a very tight collaboration with our data analytics teams,” Siebert says. “We want to integrate geospatial tools and functions in our data lake to enrich more of our common data sets with geo-referencing and analytical capabilities. So often, geospatial data is the glue between the different entities.”

As a reinsurer, as well as a primary insurer, Munich Re is keeping a keen eye on what Siebert calls “accumulation control”—using location intelligence to identify where it has the highest potential for losses. “This is so important to steer our business,” he says.

Sharing Data

Of course, location intelligence and other types of data are not just relevant within a single business—even a global reinsurer like Munich Re. Insurers and reinsurers are looking to both receive and share data with their clients and partners, as well. With the rise of natural and human-made risks across the supply chain, insurers want to know who their clients’ suppliers are—and where they operate—to accurately price risks.

Though it’s critical, the current state of data exchange is not where it should be, Siebert believes. “We have to improve,” he says. “Many of us are hoping for more open data initiatives where we have a common understanding of our risks or infrastructure.”

It is still difficult to obtain data sets that cover whole markets or whole countries, Siebert says. “Data availability is still sometimes a nightmare.”

At last year’s Reinsurance Association of the Americas (RAA) event, catastrophe response managers seemed to confirm this view. Attendees said they use NOAA and United States Geologic Survey (USGS) information as a baseline and would like other data sets to help build visibility.

“In many cases, major losses can occur due to the failure of one supplier in the value chain,” Siebert notes. “We try to visualize it, to get a better understanding [and] link the different supplier tiers according to the product chain.” To that end, Munich Re is working on creating a GIS-based solution for its clients by late this year or early 2020.

“We need a better exchange of information at all levels,” he says.

Going forward, such data will be increasingly important. A deeper understanding of location-based risk—associated with individual buildings and supply chains alike—can be an effective tool against loss from epic storms and other natural disasters triggered by climate change.

How Geoblockchain Could Curb ‘Conflict Diamond’ Trade

Blockchain and location intelligence could transform the way diamonds are marketed and sold.

Diamonds have lost some of their shine in recent years due to association with African war zones and human rights abuses. Some consumers have made it clear they won’t buy “blood diamonds” or “conflict diamonds”—those known to fund wars or support child labour. In response to consumer demand, jewellery companies are investigating ways to document the origin of their products.

The New York Times article, “You Know Your Diamond’s Cut and Carat. But Does It Have Ethical Origins?” notes that companies are monitoring product origins in greater detail using the transaction-tracking tool blockchain.

The effort could gain additional support from location intelligence delivered by a modern geographic information system (GIS). In fact, some signs point to a merger of GIS and blockchain technologies into geoblockchain—a potential innovation in how companies respond to customer and regulatory requirements.

Beyond Country of Origin

Until recently, major jewellery retailers such as Tiffany and DeBeers could only identify a gem’s country of origin. Neither the businesses nor the mines they sourced from had the technology to trace every diamond from processor to showroom. Now IBM and DeBeers have partnered with Signet Jewellers to create a blockchain-based tracking program, according to the Times article. Through that system, called Tracr, jewelers will be able to identify which mines their merchants patronize. That information will enable them to be more discerning in their purchases, rather than rejecting outright any diamonds from certain countries.

Companies in adjacent industries are also using location intelligence technologies for transparency. Nespresso, known for its single-serving coffee products, has painstakingly documented the origins of its coffee. Leaders of the company’s sustainability program use GIS to monitor the health and farming practices of 75,000 farms around the world. With location intelligence produced by GIS, Nespresso helps its farmers cultivate the most flavorful beans and get them to market faster, while updating customers on those efforts.

According to the WhereNext article, “The Business Value of Sustainability,” the program has paid dividends:

By examining and adjusting [processing] locations for farmers, the company frees up precious time and increases productivity. This impacts not only farming, but also time for education and strategic planning—the very activities Nespresso hopes will sustain its coffee crops far into the future.

Using sustainability practices and location technology to support its suppliers, Nespresso has increased its brand value as a responsible producer, maintaining customer loyalty and profitability.

Emergence of the Geoblockchain

Across industries—from diamonds to coffee—companies are striving for supply chain visibility, prompting industry leaders to explore new monitoring and reporting techniques.

Blockchain’s forte as a more secure model of transaction logging will be enhanced by GIS technology’s strength as a location-aware, cloud-based system of record. Blockchain expert Constantinos Papantoniou sees the marriage of location intelligence and blockchain as a more efficient method of monitoring supply chains:

The main advantages of geoblockchain are speed of transactions, data accessibility, and data accuracy […] With geoblockchain technology, those transactions are agreed on by all relevant parties and recorded in one distributed ledger, providing proof of location (PoL) and other details. So, the companies don’t need to reconcile disparate versions of how, where, and with whom the product traveled.

As consumer expectations shape the global economy, companies will need to perform more detailed supply chain tracking. Forward-leaning executives will be equipped to answer the call for transparency by merging blockchain with location intelligence.

This article was originally published in the global edition of WhereNext.

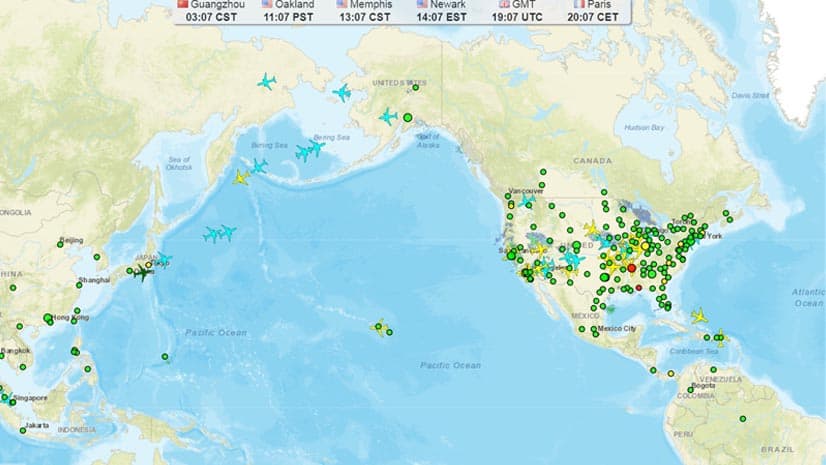

Location Intelligence Helps Keep FedEx on Time

By any measure, the numbers are staggering: 570,000 parts, 20,000 flights each month. FedEx manages it all with help from GIS.

It was late on a Thursday afternoon in November and FedEx had 160 jets in the air, flying to destinations around the globe. Most were on schedule, though a few were running several minutes late.

Each craft carried a bay full of items for eager customers from Shanghai to Memphis, Lisbon to San Francisco. Some of those packages actually included replacement parts for planes around the globe, and their on-time delivery was crucial to the carrier’s success.

Mark Yerger, vice president of material management at FedEx Express, knew where the grounded planes were and where to find the proper parts for them because of a sophisticated geographic information system (GIS). Through the system, Yerger could track up-to-the-minute progress for the fleet’s 386 jet aircraft and, with a click or two on his computer or hand-held device, drill down to learn just about anything he needed to know about a particular flight.

That level of spatial awareness, or location intelligence, empowers Yerger and team to maintain an impressive level of airplane health and availability. Last year, for instance, just 60 FedEx flights out of approximately 240,000—or .025%—failed to take off within 15 minutes of scheduled departure time because a replacement part wasn’t available in time.

Five Ps of Efficient Service

Yerger’s main concern is the operational status of hundreds of FedEx planes—and the parts that ensure their readiness. Those parts range from rivets that cost pennies to engines that cost millions of dollars. For an operation on the scale of FedEx to run cost-effectively, it can’t stock every part in every airport around the world. Instead, Yerger and his team rely on location intelligence to guide decision-making about parts and planes.

He describes their daily task as orchestrating a “very large aerial ballet” to ensure that the correct parts reach the correct planes quickly and efficiently. That choreography, he says, would be virtually impossible without the GIS-based smart maps at the heart of the FedEx tracking system.

Yerger uses five Ps to explain the ballet. “I have to have a part, a person, a plan, and a plane all in the same place at the same time,” he says.

To do that, Yerger often places a needed part on a FedEx jet that is carrying its usual cargo and is headed to the same location as the aircraft in need of repair. He can make that call by finding the correct part and then coordinating its delivery with flights in the air, or about to take off.

“If I can get that data in a very easily digestible way quickly, then I’m not going to make fire-drill calls,” he says. That often means he can avoid a last-minute rerouting or a “deadhead” flight that carries nothing but the replacement part. Those flights burn pricey fuel and pilot hours—without moving customer packages one mile.

Collaborating with IT

Yerger relies on a program FedEx has built and refined over the years, overseen by Bob Minford, the company’s vice president of airline technology. The program integrates GIS technology with the FedEx maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO) system, delivering location intelligence on smart maps. The program is available to FedEx executives, pilots, mechanics, flight planners, and just about anyone at the company involved in getting goods to their destination.

“Because of our scale and the global nature of our business,” Minford says, “we have a large number of our team members that are looking at this data.”

In order to deliver the world on time, those FedEx professionals need information quickly. “Whether they’re sitting in Global Operation Control managing all the operations, in Maintenance Operation Control, or at a maintenance shack waiting for a plane to come in, this gives them visibility” into the locations and dependencies among parts, people, and planes, Minford says. “It ties those relationships together by bringing all those disparate data sources into much better information [so] that they can make good decisions.”

That means mechanics can tap into the system using an iPad while in the hangar inspecting or working on a plane. “They could see all the manuals,” Minford says. “They could see everything about that aircraft, but they can also do every transaction that they can do on the desktop. So we’ve extended those capabilities from the desktop out to mobile devices.”

The bottom line, Minford says, is that the program allows our partners to concentrate on what’s most important.

“[W]ith the scale that we’ve gotten to and how these planes are constantly in the air, the geospatial tools really help many facets of the business to manage and to ensure that we simplify things.” That, he says, enables FedEx to “focus on the things that we have to focus on from a safety and an on-time service perspective.”

Having timelier access to more granular information, having the problems jump out of the screen… means that my maintenance specialists can absorb much more information more quickly than by looking at giant spreadsheets.

Mark Yerger, VP of material management at FedEx Express

Customers Want Speedy Delivery

“When it absolutely, positively has to be there overnight,” a FedEx tagline first deployed in 1978, has never been more apropos in the delivery and logistics business than right now.

While consumers still shop mostly in stores, the balance is shifting. The percentage of goods ordered online continues to grow, and with it, expectations for fast—sometimes even same-day—delivery.

That demand led to a 17 percent spike in parcel volume during 2017, according to a Supply Chain Dive article. Additional double-digit gains were predcited through 2020 across more than a dozen major economies. FedEx connects with 99 percent of the global GDP through 14 million air and ground shipments each business day.

Retail sales, one of the financial drivers of parcel companies, were estimated to rise almost 5 percent in 2018 over 2017’s nearly $5.7 trillion, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

If global trade skirmishes escalate into trade wars this year, that could put a crimp on commerce. But the long-term trend is toward more goods being delivered quickly all around the world.

Long Haulers to Short Hoppers—Coordinating Moving Targets

Regardless of politics and trade negotiations, certain FedEx officials spend the majority of their day ensuring that the company’s fleet of almost 700 jets—ranging in size from long haulers like the Boeing 777 to smaller mid-range jets—are ready to fly around the clock.

Yerger relies on the company’s location intelligence system to track the fleet and make sure planes are where they are supposed to be, safely and at the right time. That’s no small feat when FedEx has aircraft circumnavigating the earth 20,000 times each month.

Coordinating FedEx maintenance worldwide with location intelligence

Like any executive who must make sensitive decisions in short order, Yerger looks to the GIS-powered system to find signals in the noise. As he explains, “The computer and the picture tell you what your biggest worries are, and/or what your easiest solutions are in a way that’s much easier for a human to digest.”

Planes on time, for instance, appear in green on his smart device or desktop, while those that are lagging are red. He can see flights all over the earth in one glance, or limit his view to aircraft associated with a particular region or airport.

That flexibility saves him and his fellow managers, as well as the mechanical staff that reports to him, precious minutes for other pressing decisions.

Data to Save Time

In essence, the FedEx system replaces a slew of documents with an integrated smart map, Yerger says.

“I don’t have to go thumb through 130 or 140 lines of a spreadsheet to figure out when did [the flight] depart, when was it supposed to depart, what’s the turnaround time, what’s the window, and when it’s expected back to [FedEx headquarters in] Memphis,” he explains.

One of Yerger’s primary responsibilities is avoiding the dreaded and costly AOG—an aircraft on the ground, unable to fly. During that November afternoon, Yerger checked the system to discover that only two of the planes in the air were behind schedule enough to cause concern. Both needed repairs that might not be completed in time for the scheduled departures. As a result, other planes might have to be used as replacements. In the industry, that’s called a tail switch.

On paper, the variables involved in the aerial ballet seem overwhelming. For instance, not all repairs are created equal. Some are mission critical and must be made before the airplane can lift off again. Others are less pressing, giving Yerger and team the luxury of time.

Then there are the parts themselves. FedEx manages more than 80,000 part numbers across its air operations. It keeps at least one part in each of about 575,000 bins at airports worldwide. Its nearly 700 planes visit 175 airports worldwide.

When one of those planes needs repairs and the five Ps aren’t aligned, Yerger’s team uses the logistics system to find the correct replacement part and coordinate its delivery to the aircraft’s next stop. Yerger likens the process to passing a hockey puck where a teammate will be instead of where he is.

To meet that “moving demand,” FedEx annually sends more than 850,000 shipments of parts. It’s a massive job made faster and more reliable by location intelligence.

When I think about GIS, I think about a couple variables—not only [the] location of our aircraft, but GIS also provides us with time. And those are two variables that are extremely important to the business at FedEx.

Bob Minford, FedEx VP of airline technology

Artificial Intelligence Predicts Maintenance Needs

Yerger, Minford, and their FedEx colleagues know as well as anyone how important speed is to customer satisfaction and competitive advantage. The location intelligence system they rely on was built to help them make the right decisions faster.

And despite its success, FedEx continues to find ways to wring idle minutes out of its operations. The constantly evolving system, Minford says, now incorporates artificial intelligence, or AI, that forecasts when a plane needs replacement parts or a maintenance checkup.

AI’s predictive capabilities, combined with the geospatial programs that monitor where a plane is, amount to “almost the holy grail for a maintenance operation,” he says.

The company is also exploring maintenance innovations like using drones to perform airplane inspections that are cumbersome for humans to undertake. The top of a 777’s tail, for instance, can stand 60 feet above the ground. A mechanic piloting a drone with high-definition cameras now can detect hail or lightning damage faster than ever, while standing on the tarmac.

“As new things come up, we can just layer those relationships on,” Minford says, “and the map visualization simplifies it so that humans can understand it.”

That awareness of information tied to time and location, he says, allows Yerger and other FedEx professionals to act quickly on issues flagged by the system. “But they also see the big picture,” Minford adds.

The Hidden Factor Affecting Employee Health

It’s time for employers to wake up to an overlooked–and costly–aspect of employee health.

Nearly 80 percent of big businesses, and a growing number of small and midsize companies, self-insure their employees’ health coverage. On average, that costs a business more than $13,000 per employee per year.

Most companies have also instituted wellness programs to improve the health of workers and decrease healthcare costs. Unfortunately, many wellness programs are not as effective as they could be because they overlook a key data point: the health implications of where an employee lives.

Research has proven that location carries with it many social, community, and environmental conditions that affect a person’s health—also known as social determinants of health. The impact of these factors reaches far beyond one’s home. It follows us everywhere we go, including into the workplace and the healthcare system.

Experiments in places such as Camden, NJ, have shown a greater than 50 percent reduction in healthcare costs for patients in certain geographies. With that in mind, employers who use location intelligence to analyse social determinants of health can create data-driven wellness programs designed to overcome barriers to good health and potentially cut costs.

While corporate executives routinely use data to drive business decisions, many of those executives are still investing in generic wellness programs designed without employee context.

Innovation in Your Inbox

Sign up for the Esri Brief, a biweekly email that connects senior executives and business leaders with thought-provoking articles on location intelligence and critical technology trends.

The US Centers for Disease Control says too few employers are using effective, science-based workplace health programs that address unique challenges faced by employees. A geographic information system (GIS) allows companies to identify social determinants of employee health by creating a wellness map that identifies top inhibitors of a healthy lifestyle based on where employees live. Such technology can also reveal health-promoting resources in those same communities.

Today’s Corporate Healthcare and Wellness Landscape

In 2016, the number of companies that self-insured at least one health plan reached 41 percent, up from 30 percent in 2000. Self-insurance has the potential to offer employers significant financial advantage, but only if they can control costs.

Corporate wellness programs were introduced in the mid-1970sto address employers’ cost concerns by encouraging employees to adopt and maintain healthy behaviours. Johnson & Johnson’s trailblazing Live for Life program began in 1979 and included a questionnaire and physical exam. The company subsequently provided employees customized wellness support including fitness, nutrition, and stress management tips.

Since then, the market for corporate wellness has grown significantly. Ninety-nine percent of firms with 200 or more employees offered at least one wellness program in 2013, according to one study. Of those employers, 69 percent offered gym membership discounts or on-site gyms, 71 percent offered smoking cessation programs, and 58 percent offered weight-loss incentives.

The reasons for such programs are clear. For example, compared to employees of healthy weight, obese workers may incur more than double the cost for healthcare, workers compensation, and short-term disability. That could add up to an additional $4,000 per year, per employee, one study found. Additional health complications such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol drive that number even higher.

The Effects of Location

Location can affect a person’s health in many ways, including:

- Access to healthcare, services, education, and healthy food

- Community characteristics such as crime rate, traffic, and availability of public transportation

- Environmental exposures like pollution, pollens, and toxic waste

- Socioeconomic factors that affect a person’s ability to attend medical appointments, access healthy food options, or exercise in a safe place

The Missing Element: Location

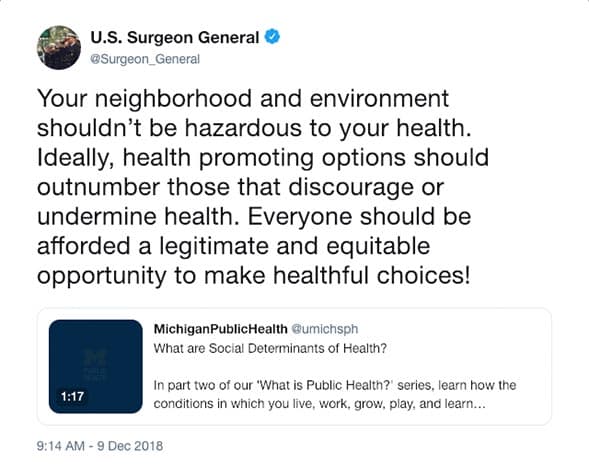

Extensive research has been conducted in recent years proving that a person’s environment directly impacts the ability to live a healthy lifestyle. The world is beginning to take notice, as evidenced by a December 2018 tweet from U.S. Surgeon General Jerome M. Adams:

Ana Lopez-De Fede, Ph.D., research professor and associate director of the Institute for Families in Society at the University of South Carolina, has studied how a person’s place of birth and where they live influence their work environment.

For example, in a single-vehicle household, one family member typically takes that vehicle to work, limiting the rest of the family’s access to resources like grocery stores, workout facilities, and libraries. Those family members miss medical appointments more frequently, and the lack of routine visits ultimately leads to a higher rate of preventable emergency rooms trips and inpatient hospitalizations.

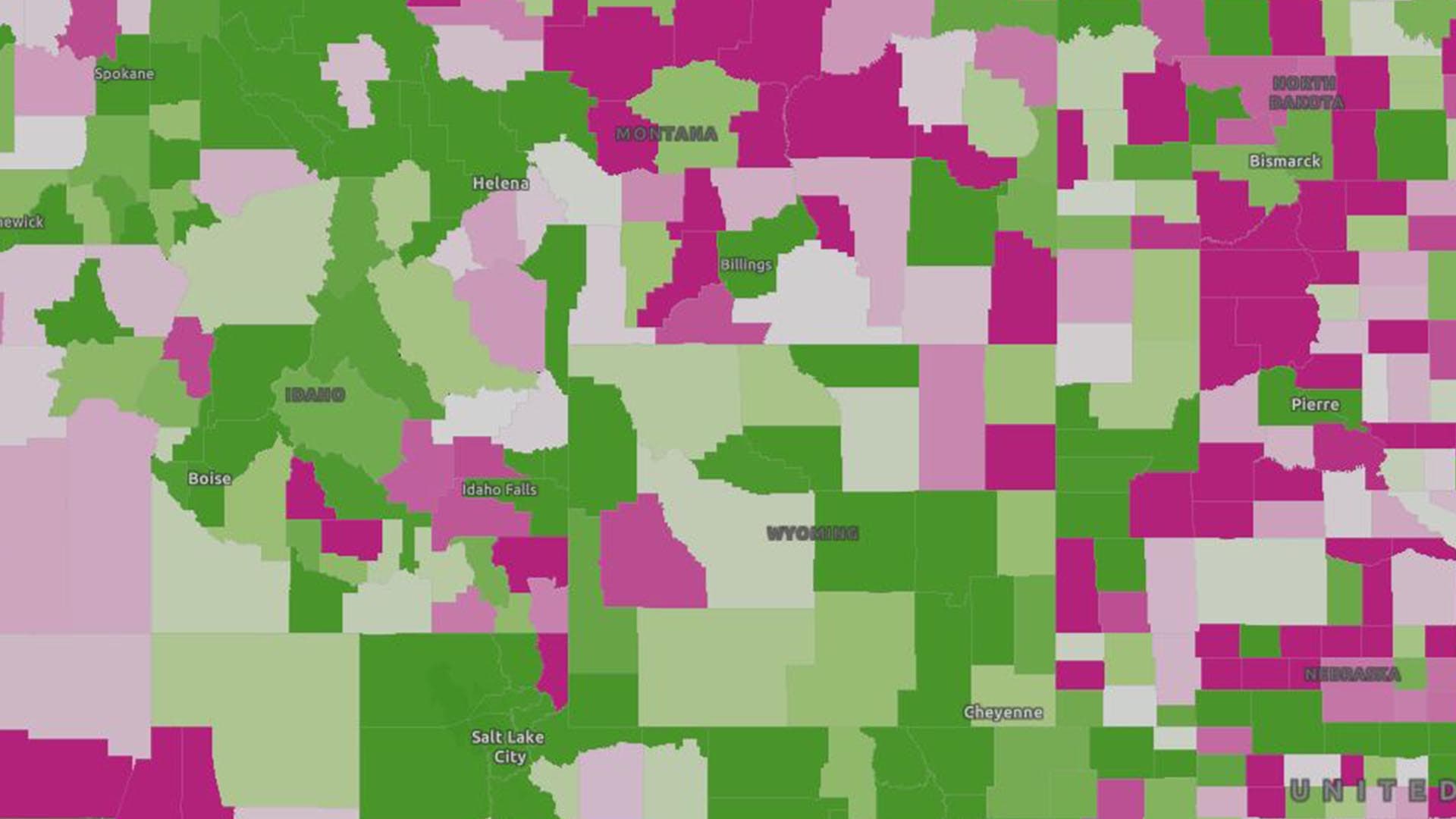

But the single-car phenomenon is just one of many factors that influence employee health. Others include the rate of particulate matter in the air where they live, access to exercise opportunities and healthy foods, and the ratio of local primary care physicians. Plotting these social determinants of health on a GIS-driven map can give employers a better sense of what ails employees—and what drives healthcare costs. That awareness often leads to innovative remedies.

To explore a few of the social determinants of health in your neighbourhood, click through this map. (To view each factor on its own, deselect all other factors.)

“Utilizing GIS, an employer can determine the reasons behind high medical costs by understanding context as it relates to employees’ geographic location,” says Lopez-De Fede. “An employer can then determine reasonable costs of healthcare and create contextually relevant wellness programs that improve the quality of life of their employees, while also addressing those high medical costs.”

Academic studies have confirmed Lopez-De Fede’s findings. The National Research Council found that a variety of place-based influences can affect health, including physical circumstances (e.g. altitude, temperature, and pollutants), social context (e.g., social networks, access to care, perception of risk behaviours), and economic conditions (e.g., quality housing and access to health insurance).

Another study found that the increasing epidemic of obesity and chronic disease is likely influenced far more by food and eating environments than by individual factors such as knowledge, skills, and motivation. The finding underscores the importance of making the healthy choice the easy choice, a mantra in the public health community.

Location Viewed as the “Seventh Vital Sign”

Business executives can take a cue from healthcare practitioners such as Lopez-De Fede, who are now examining location-based determinants of health for each patient.

Southern California’s Loma Linda University Health has created personalized “wellness maps” for each of its patients, based on the belief that location is one of a patient’s vital signs.

Loma Linda creates the maps using GIS technology, digitally layering information on top of geographic locations. Each patient can access a personalized GIS wellness map through Loma Linda’s patient portal for electronic health records. On the map, the patient sees her personal health resources (clinics, providers, labs, and pharmacies) as well as community resources such as bus transportation routes, and places to exercise or purchase nutritious food. Each map is updated as the patient’s diagnosis changes. For example, an expectant mother will see a very different map than a patient with diabetes.

For some employees, the opportunities for healthy choices are significantly limited based on where they live, which can ultimately impact the cost of their healthcare.

The County Health Rankings & Roadmaps Project

Utilising Location Intelligence to Improve Wellness in the Workplace

Self-insured businesses are already driving healthcare innovation in the workplace by offering new care models like telemedicine and on-site clinics. The next step will be using GIS-based location intelligence to develop more effective health and wellness programs.

Dr. Lopez-De Fede says employers should begin by asking themselves questions related to their employees’ unique health challenges and associated costs, such as, Where do my employees live? What’s going on outside of the office?

GIS helps employers answer these questions by analysing health-related information in the context of location. Data is gathered at a group level to protect employee privacy, and its analysis can help employers find solutions to health barriers. For instance, if employees aren’t picking up prescriptions or are missing doctor appointments, an employer could create an in-network pharmacy closer to the office and create flex time for appointments.

Once employers have used location intelligence to identify employee barriers to health, they can create more effective wellness programs that address location-based challenges faced by employees. Examples include:

- Develop key partnerships in employees’ communities to improve access to and awareness of wellness resources such as pharmacies, fitness clubs, grocery stores, and transportation resources. (The North Carolina Institute of Public Health in partnership with the Carolinas HealthCare System is doing this for its patients, using GIS.)

- Add to the insurance network pharmacies and health clinics in underserved neighbourhoods

- Allow employees to have groceries delivered to the office and provide them a place to store them

- Provide free exercise classes in the workplace, and hold a 5K walk/run in underserved communities

- Decrease stress associated with long commutes by offering shared transportation options (e.g., vans, carpools)

- Create a teacher mentorship program to transfer best practices from healthy communities to less-healthy communities

- Offer an app that lets employees and their families build an exercise routine based on nearby green spaces, bus routes, gyms, bike shares, sunrise/sunset times, and more

- Create personalized wellness maps that show employees resources in their communities

Wellness programs are often designed with the best intentions and the hope that they balance good health with good economics. But in the age of data-driven decisions, employers can use more than hope to drive results. Innovative, self-insuring companies are now using location intelligence to help promote employee health, reduce costs, and improve productivity.

Opportunity Awaits Employers That Overcome Location Bias

In a tight job market, every hiring advantage is important. Companies that reduce location bias could gain an edge.

On a résumé, the second thing an employer learns about someone is where they live. A recent study tested the effect that commute distance has on an applicant’s chance of being hired. It found that hiring managers are biased against those who live farther away.

The research, conducted by University of Notre Dame economics professor David Phillips, involved sending more than 2,000 fictional résumés to low-wage employers in Washington, DC. Phillips carefully chose résumé addresses for each job opening and balanced the mix of applicant-workplace proximity and the affluence of the job seeker’s neighbourhood to see how the location of the applicant’s home influenced invitations to interview.

The results: applicants living five or six miles farther from the job received one-third fewer callbacks than those who lived closer.

Distance versus Affluence

The research was designed to test the “spatial mismatch hypothesis,” which argues that the tendency of the urban poor to live far from jobs makes it difficult to find employment, thus perpetuating poverty.

The research offered some solace for job applicants and some insight for employers. Refreshingly, researchers found little significance between the affluence of an applicant’s address and the rate of callbacks, indicating that those in poor areas weren’t purposely being overlooked. Instead, the perceived issue of reliability in a long commute was deemed the deciding factor.

Researchers acknowledged that avoiding applicants with long commutes makes some sense from an employer’s point of view. Neighborhoods with few transit options and high transit costs can translate into a high turnover for low-wage jobs. Long commutes have also been shown to increase absenteeism.

But with location intelligence and creative thinking, employers might find ways to mitigate the impacts of distance.

[To learn more about the effects of location intelligence on a business, read this e-book.]

Influencing Upward Mobility

With today’s booming economy and low unemployment rates, employers face difficulty staffing up to meet peak demand.

Some companies have used a geographic information system (GIS) as a competitive intelligence tool and information resource for finding staff near retail locations.

Location intelligence generated by GIS can also help employers locate pockets of willing and able workers in areas impacted by urban revitalization. The increased cost of living in revitalized areas has pushed low-income, minority communities farther away from economic opportunity and into neighbourhood with little or no access to reliable, affordable transportation.

To access workers and help mitigate the challenges of long commutes, employers might consider flexible options, including four-day workweeks and flexible job hours to avoid busy travel times.

Location Intelligence Maps Solutions

Several commentators suggest that employers would be wise to consider offering shuttle services or public transportation vouchers to improve worker reliability. A modern GIS helps companies map optimal routes to decrease commute times—something that the logistics experts at UPS can attest to.

In addition, companies looking to bolster a social good campaign could focus on hiring in an area where they would have an impact on upward mobility. Location intelligence reveals demographics in specific areas to facilitate this kind of analysis.

Lyft recently announced a partnership with a nonprofit to start the Grocery Access Program, with $2.50 flat fares to grocery stores for families living in food deserts. The resultant improved mobility is helping to address the lack of access to healthy food, a well-documented problem of the urban poor.

A similar effort—one that leverages location intelligence to connect underserved groups with available jobs—could help employers address their own needs and do well while doing good.

Changing Demographics Ripple through the Supply Chain

Businesses are adjusting supply chains to match shifting demand, using demographic insight into a changing world.

Major demographic shifts will alter the makeup and preferences of consumers worldwide in years to come, and companies that maintain global supply chains must take note.

In a recent CSCMP’s Supply Chain Quarterly article, two Penn State University professors and a VP of supply chain operations at the Hershey Company examined three significant demographic changes that they expect to occur, and the effects those changes could have on the supply chain.

Getting ahead of a Global Shift

Global shifts in population will affect where and how people live and work, according to the article’s authors, who expect the changes to be measured across three primary dimensions:

- Magnitude—The rate of global population growth will decline, with Africa and Asia the biggest contributors to growth

- Structure—Longer lifespans will dominate, religious makeups will shift, and middle-class growth will accelerate in Asia

- Migration—Internationally, the movement of migrants will reverse—flowing to Europe instead of from it—while on the local scale, migration to urban areas will increase

The changes will affect both ends of the supply chain and challenge executives to rethink not only where customer demand will be, but also where companies should locate production to meet that demand.

As manufacturing and logistics expert Cindy Elliott observed in a recent WhereNext article, “Execs must grasp not only where consumers are now, but where they are going—predicting business opportunities based on emerging trends in precision demographics.”

A New Form of Business Intelligence

Reliance on location intelligence is rising steadily in business circles, as executives warm to the value of location-based data. Visit this e-book for detailed use cases.

Leading companies are paying attention to these trends in consumer movement and preferences, and using location intelligence to proactively adjust their supply chains.

Analysing Local and Global Demographics

In the Supply Chain Quarterly article, Hershey Company VP of supply chain operations Jason Reiman noted that his company is making changes throughout the supply chain in anticipation. As part of its analysis, Hershey first examined where it expects future customers to live, then planned production locations close to the areas of increasing demand. Next, it identified a suitable workforce in those new areas.

For businesses conducting similar long-term planning, location intelligence can be a key asset. As Elliott explained:

Executives can aggregate insight from global down to neighbourhood markets to understand how, where, and at what pace consumer preferences are changing. They can then pinpoint appropriate shifts in their business models and outpace the competition.

The engine for that analysis is often a geographic information system. GIS technology ties digital information to a place, allowing retailers to examine competitor locations, insurance companies to assess claims across neighbourhoods, and logistics providers to plan efficient delivery routes. Global manufacturers use the demographic capabilities of GIS to gauge where customers may move in coming years.

Building a Complete Supply Chain Strategy

Globally, growth was slowing in Hershey’s traditional markets in the United States, Europe, Japan, and Australia, the authors note. The company saw an emerging city-dwelling middle class in Asia and the Middle East, a cohort predicted to grow over the next 15 to 20 years.

These were potential new consumers with disposable income to spend on Hershey’s confectionary products. To get close to that demand—and key resources such as cocoa liquor and sugar—the company established a new manufacturing plant in Malaysia.

As the authors explain, Hershey then examined local demographics near the city of Johor, Malaysia. They identified a potential workforce that was young, educated, and productive. Delving deeper into the psychographics of the new workforce helped the company plan a facility layout and operating procedures that complemented local training needs, languages, and religious preferences.

The location intelligence that comes from demographic analysis was once the exclusive province of marketing executives seeking to craft messages for certain groups of customers. As Hershey’s tale illustrates, such insight now plays a role throughout the supply chain.

On the demand side, companies use GIS-powered location intelligence to understand changing consumer needs and adjust their presence in various markets. Those adjustments ripple through to the supply side, influencing where the company sites production facilities. They also help facility planners and operators understand and accommodate the local workforce.

The demographic shifts that Hershey and other companies foresee aren’t short-term changes. They will have significant and lasting effects on the supply chain. Executives who enlist location intelligence to plan for those changes now will likely find themselves with the right supply chain balance down the road.

A Little-Known Alternative to Wooing Amazon

Across the nation, economic development agencies are quietly nurturing small companies while complementing efforts to attract big corporations.

When Amazon announced in September 2017 that it was looking for a second headquarters location, the news set off a 13-month competition that had 238 cities outbidding each other to woo the internet retail giant with billions in tax and financial incentives. Some observers watched with chagrin. They knew a different way to grow local economies.

The eventual winners—Long Island City, New York, and Arlington, Virginia (along with Nashville, which will host a new operations centre)—awarded Amazon more than $2.4 billion in local and state tax breaks.

The passion with which many cities pursued the expected prize of 50,000 new jobs showed in Columbus, Ohio’s offer of $2.8 billion in direct tax incentives—more than the three winning cities combined. Detroit and Michigan upped the ante to $4 billion and New Jersey was willing to provide $7 billion in city and state tax credits.

But an analysis by The Atlantic highlighted the fact that companies with big tax incentives don’t always meet their goals and may still lure cities into bidding wars every few years. The Brookings Institution also found that many incentive packages do not require the sought-after company to invest heavily in job training for local residents or in improving their living conditions.

Pursuing Titans or Nurturing Homegrown Businesses

For cities that can’t—or don’t want to—compete for market giants, there’s another proven option: economic gardening.

“Chasing the big corporation is expensive, it’s time-consuming, and the likelihood of being awarded that business to your particular community is pretty low,” says John Gendron, who manages the Kansas Economic Gardening program within the Kansas Center for Entrepreneurship, known as NetWork Kansas.

Though rarely in the national spotlight, economic gardening is the lower-cost alternative, free from tax breaks or complicated agreements with multinational corporations that could still pull up stakes if a better deal emerges elsewhere.

The economic development agencies that practice it focus on helping moderate-sized local businesses grow. They do so through research, business consulting, and a technology called a geographic information system (GIS). For companies small and large, GIS reveals new market opportunities, uncovers subtle consumer trends, and tracks demographic shifts in locations across the country and around the world. Economic gardening advisors suggest how companies can turn that deep analysis into profitable action.

The result is locally cultivated economic growth.

Economic Gardening Grows Local Businesses

In Florida, for example, GrowFL used economic gardening to help generate nearly 11,000 net new jobs between 2009 and 2015. Those companies added more than $81 million in net state and local tax revenues, meaning Florida received a return of more than $9 for every dollar invested in economic gardening.

NetWork Kansas’s Gendron, who has worked in economic gardening for nine years, says that this less splashy option often can “spike revenues and create jobs at a lower cost while supporting the businesses right in your backyard.”

Economic gardening can’t promise 50,000 jobs from one company, as Amazon did. But 235 cities spent more than a year and hundreds of thousands of dollars to pitch the internet powerhouse and ended with little to show. Meanwhile the Kansas Economic Gardening Network only needs to spend 45 days and invest services worth $4,500 to help a local company add an average of 12 new jobs and $1.5 million in new sales. Over time, that process can create meaningful job growth without sacrificing local tax revenue.

A Young Company Grows up through Location Intelligence

Rodney Greenup had developed a successful business in Louisiana by providing facilities management and construction services to the oil and gas industry, which requires security clearance for all contractors and subcontractors.

Like most successful entrepreneurs, Greenup relied on great instincts to get his business started and stabilized. He also wanted to keep growing. He thought the simplest way would be to market the services of Greenup Industries in as many states as he could. He was ready to open offices elsewhere and initiate a wide-ranging marketing campaign when he came across the Louisiana Economic Development (LED) agency and its programs. During the approximately 45-day analysis and consultation program with LED, Greenup learned a lot that surprised him.

Location Intelligence: A Smarter Approach

Organizations in many industries use location intelligence to improve their operations. To learn about them, read this e-book on location intelligence.

The agency delivered a slew of economic gardening services, including location intelligence on GreenUp’s customers, competitors, and markets. That GIS-powered insight is often the most important tool in business growth. In simplified terms, GIS is a form of business intelligence that integrates demographic, customer, and economic data into digital maps. Those maps often bring to light hidden or little understood relationships between a company and its current or potential customers.

LED’s research, business consultation, and GIS-based maps led Greenup in new directions.

“Going in, we initially thought we would try to get every client that we could possibly encounter,” Greenup says. “But economic gardening really focused our attention and showed us which potential clients were predicting the largest amount of growth and the biggest spend on their facilities for the next three years.”

Economic Gardening Took Root after Layoffs

Chris Gibbons, CEO of the National Center for Economic Gardening, is credited with helping to originate the idea of economic gardening when he was director of business and industry affairs for the city of Littleton, Colorado, in the 1980s. The idea stemmed from the need to replace approximately 7,000 jobs lost when Littleton’s major employer, a defence contractor, laid off employees into a local economy that could not absorb them.

The methods Gibbons helped develop to stimulate growth set a pattern of similar successes across the nation. During the 20-year period that followed the massive layoffs, Littleton doubled jobs from 15,000 to 30,000 and more than tripled sales tax revenue from $6 million to $21 million—all without recruiting any outside companies, offering tax incentives, or experiencing a large population increase.

Gibbons says GIS-driven insight on potential customers, competitors, and markets allows a typical small business to sharpen its strategy and increase its growth rate from 3–5 percent to 15–35 percent.

[Economic gardening is] an alternative way of doing economic development that focuses on growing local stage-two companies as opposed to attracting outside companies. Both methods work, but I really believe strongly in what we do.

Chris Gibbons, National Center for Economic Gardening

Local Businesses Generate High Percentage of New Jobs

Nationally, the typical business that is a candidate for economic gardening has from 10 to 100 employees and sales of $1 million to $50 million. (Ranges vary in urban and rural areas.)

These are businesses that no longer face a day-to-day struggle to survive and whose owners want to keep expanding but don’t know the best way to market beyond their own location. Often called second-stage businesses, they also happen to generate a disproportionately high percentage of new jobs.

Stage-two businesses may have represented only 17 percent of all US businesses from 2005 to 2015, but they created more than 35 percent of the jobs and sales, according to the Edward Lowe Foundation, which supports the entrepreneurship of second-stage companies.

Digital Watering Holes

One way Louisiana Economic Development helps stage-two companies find opportunities to expand is to show them the digital “watering holes”—websites, blogs, and social media—that potential customers or competitors frequent. This helps young companies stay up-to-date on relevant trends and identify marketing channels that may contribute to their expansion.

Communities in 25 states from California to New York and from Minnesota to Texas have found economic gardening a successful way to grow locally owned and operated businesses. Yet while it’s seen as a cost-effective way of helping homegrown companies expand, it’s often a supplement, not a replacement, for other approaches.

LED, for example, has adopted a multipronged strategy that looks for opportunities at both ends of the business spectrum. The agency works diligently to attract large corporations to the state and retain its current businesses, and it works just as intensely to accelerate the growth of local companies through economic gardening.

For Greenup Industries and others that have gone through the LED program, results have been impressive. Louisiana companies participating in LED’s economic gardening program have collectively added nearly 2,000 net new jobs and increased their gross revenue by $338 million. LED, like GrowFL, calculates a return of more than $9 for every $1 invested in the effort.

“Typically, when we grow what we have, a number of things take place,” says John Matthews, senior director of small business services for LED. “One, the businesses are here already, so they more than likely are here to stay. Two, they understand the culture of Louisiana. And, three, they’re more readily supportive of the community and its quality of life.”

A Michigan pie company learned to increase sales through GIS-powered location intelligence that showed where Michigan college sports fans tended to watch games in West Florida sports bars.

Saving Marketing Costs by Focusing on Core Services and Concentrated Areas

Through GIS technology, economic gardening teams have access to databases that most stage-two business owners don’t know exist. That data can be layered onto smart maps to reveal economic and consumer patterns. For Greenup Industries, the economic gardening team used market research and GIS technology to illustrate some surprising facts.

Not only hadn’t Greenup realized his core business contained services that would be transferrable to the automotive, food services, and pharmaceutical industries, but also that those same businesses were growing at a faster rate than his oil and gas clients.

Moreover, by using location intelligence to find clusters of potential new clients within those overlooked industries, LED was able to show that he had many more opportunities in the Gulf Coast states of Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida than he had imagined. It caused Greenup to rethink his strategy of opening offices in far-flung locales.

“You have to listen to the data,” Greenup says. “Economic gardening really clarified a lot of things for me… I really thought I had a good plan for where I was going, but what they did was make me focus and realize my other plans would be distractions and an inefficient use of time and money.”

Variety of Crops Arise from Economic Gardening

The array of businesses helped by economic gardening stretches over many market sectors and includes both B2B and B2C companies.

- In Louisiana, LED showed a company that manages the vegetation affecting powerlines how to expand significantly, and it also helped map an expansion for a software company that developed an app that restaurants can use for delivering to-go orders.

- The National Center for Economic Gardening has helped many companies expand nationally while keeping their local roots. One example: A Michigan pie company learned to increase sales through GIS-powered location intelligence that showed where Michiganders had migrated, where customers with similar tastes might live, and even where Michigan college sports fans tended to watch games in West Florida sports bars.

All are reminders that job creation and revenue growth through smaller businesses can add up over time and even begin to compare favourably with efforts to land a giant corporation. And some second-stage companies nourished by economic gardening will become tomorrow’s household names.

Having grown larger through the crucial location intelligence that economic development agencies provided, these companies may be more likely to stay rooted in their hometowns.

“We need to nurture second-stage companies,” says Matthews of Louisiana Economic Development. “Because the data suggests they are the companies that will create jobs today and in the future.”

Halo Forecasting with AI: A Major Leap in Retail Planning

A long-coveted forecast comes to life for retailers, using AI and the geospatial cloud to predict brick and mortar and online sales.

In the past several months, several globally recognized retailers have experimented with a new way to plan business expansion. Simple in concept yet revolutionary in its approach, this new business tool answers a long-held need.

Innovation in Your Inbox

Sign up for the Esri Brief, a biweekly email that connects senior executives and business leaders with thought-provoking articles on location intelligence and critical technology trends.

At its core is a powerful prediction engine that calculates the revenue a retailer can expect from any potential market—or series of markets. Its distinguishing feature, though, is the ability to see across channels. In an era when brick and mortar sales and online purchases can seem like independent phenomena, this tool reveals how they’re connected.

The technique is called halo forecasting, and it combines artificial intelligence and the power of the geospatial cloud to change the way executives plan a business.

AI Moves Fans in and out of SunTrust Park

When the Atlanta Braves take the field, the Cobb County police force deploys GIS-based location intelligence and AI to keep fans happy and safe.

As many as 41,000 people depart SunTrust Park on any given summer night after a game hosted by the Atlanta Braves baseball team. Those departing fans often see nothing but green lights at key crowded intersections, thanks to a system built on location data and artificial intelligence (AI).

The goal at every game is to move people on foot in and out of the stadium in the safest, most expeditious manner. That happens routinely because the Braves organization collaborated with Cobb County Police Department and Cobb County Department of Transportation (DOT) officials to create a control centre deep within the ballpark that leverages advanced technologies, including AI and a geographic information system (GIS).

The control centre, run by Cobb Police Lt. J. D. Lorens, features eight 42-inch video screens and more than 70 live camera feeds monitoring the ballpark’s pathways and surroundings. Those feeds also track 30 critical intersections near the park, including three crucial traffic-prone spots where pedestrians and cars come together. With so much to monitor and limited resources to manage it all, quick insight and fast action are critical to keeping fans and residents safe and happy.

Lorens spends most Braves games in the middle of SunTrust’s bustling command centre. In addition to managing all aspects of stadium security, he and his officers synchronize the flow of vehicular and pedestrian traffic near the stadium.

Since the first pitch of the 2018 season, they’ve had help from a GIS-powered operations dashboard bolstered by artificial intelligence. The GIS enables Lorens and his team to visualize spatial relationships—the location of every traffic light and camera in the area, and the distance between them. That location data is a critical input to the IBM Watson-based AI system, which analyses foot traffic through real-time video feeds.

Together, the two technologies gauge the flow of pedestrian traffic by reading the number of pixels on screens, rather than faces or the actual number of fans. As the density of fans heading toward a particular intersection grows, the AI system recommends a change to the relevant traffic light sequence outside the ballpark.

AI Enables Split-Second Decisions

The system has its roots in a conversation between Lorens and members of the Cobb County GIS team. Lorens recalls the team asking how he knew when to adjust traffic lights based on pedestrian movement inside and outside the stadium.

Artificial Intelligence Expands

From baseball stadiums to the boardrooms of growing retailers, artificial intelligence is helping organizations make important decisions. Explore this e-book for other stories of AI’s contributions.

As he described his process—which drew mostly on experience and educated guesses—the team asked, “Would it be helpful for a computer to tell you when to do this?” Lorens jumped at the idea. “I’ve got 70-something cameras I’m watching [and] 30 critical intersections,” he explains. “It allowed me to divide my attention amongst other things.”

Now the AI and GIS dashboard provides advance notice of potential pedestrian and vehicular traffic bottlenecks. Once the system flashes a predictive alert, Lorens can send an officer or two to manually direct pedestrians and motorists to speed the flow.

The most immediate payoff of merging AI and GIS at SunTrust Park is something every traffic-obsessed resident of metro Atlanta can appreciate. Lorens and his crew routinely empty out the stadium and surrounding area within 35 minutes or less during weekday games. Compare that to an hour—and often more—at the Braves’ old home, Turner Field in downtown Atlanta. That’s a big deal, especially in a region plagued by decades of traffic congestion.

AI-derived predictions that are tied to location augment human intelligence and interactions—by keeping stakeholders informed in advance.

Location Intelligence Critical to Speedy Development Plan

The Braves recently completed their second season at SunTrust field, which in early 2014, was nothing more than an empty 60-acre lot about 10 miles northwest of downtown Atlanta.

The new ballpark, along with surrounding retail, office, and commercial space, was built in little more than two and a half years, in time for the Braves’ opener in April 2017.

Starting from scratch allowed the Braves, Cobb County, the state DOT, and other government agencies and private companies to collaborate on creating and managing what essentially became a new town near the confluence of two major highways—interstates 75 and 285.

“Because [the land] was not developed,” says Jennifer Lana, Cobb County’s GIS manager, “the county and the Braves had the opportunity to install a lot of new technology to do management and training. . . We jumped forward a few years in technology.”

Cobb County had already mapped the site in its GIS, effectively creating a 3D digital twin of the area. The twin—now used extensively in the SunTrust Park control room and the AI system—allowed site planners to quickly model zoning scenarios for the entire land parcel.

“[W]e did use GIS for sharing plans, addressing the roads, naming the sites, because it was like a new city,” Lana says. “All the zoning changes went into GIS. Every utility line that we installed, every storm water pipe, every valve, all the fire marshal’s plans.”

Without GIS, AI, and related programs, the ambitious construction schedule would not have been possible, says Sharon Stanley, who oversees all information technology for Cobb County.

Recalling a conversation she had with members of her tech team back when the stadium first opened, she says, “We’d have gotten here without the machine learning and the [artificial] intelligence, but it would’ve been two years from now.”

Stanley says she considers GIS and AI—and any other type of information technology—to be tools that can accelerate the pace of projects large or small. “Citizens don’t give taxes to get IT,” she says, but the agencies that serve those residents benefit every day from modern technology.

An intelligent system powered by GIS and AI adapts to changing situations, making predictions that are intelligent and comprehensible by any decision maker.

AI Likely a Job Creator

Some observers fear that AI in the workplace could replace humans and result in higher unemployment. Chatbots, for example, have taken the place of some customer service jobs.

But research from analyst firm Gartner maintains that AI will create two million new jobs by the year 2025. AI, Gartner concedes, likely will eliminate middle- and low-level positions but will end up producing skilled employment opportunities, especially in management.

Just as search engines revolutionized the speed of information discovery and knowledge sharing, AI and location data are accelerating business activities by performing some tasks faster than humans can, with more data. The benefit isn’t simply faster decisions, It’s smarter decisions.

Gartner predicts that AI will be used to augment human capabilities, as it does at SunTrust Park. For instance, Lorens routinely relies on AI to keep him informed and ahead of any potential crowd and traffic issues.

Traffic Concerns Morphed into Pedestrian Worries

When the Braves announced in 2013 that the club would be moving from Turner Field to a planned stadium in Cobb County after the 2016 season, one of the biggest worries was traffic. How would people get to the stadium without overrunning local roads and interstates?

Traffic engineers decided to widen some Cobb roads, then placed parking garages and spaces 360 degrees around the stadium, near main road arteries. Fans could then be ferried by shuttles to SunTrust Park or walk across one of the two pedestrian bridges that span the highways.

Critical to the plan’s success was the ability to ensure that people could get to and from the stadium safely without fretting about traffic. This is where the ballpark control centre and the AI-GIS collaboration came into play. They help Lorens and team keep fans moving around SunTrust Park.

Situated in that command centre, Lorens can also use the dashboard to train officers and traffic operations personnel on the best traffic flow strategies.

“[The system] gives the same information every time, no matter who’s looking at it,” he says. “So, somebody else would be able to go in and do what I do without me having to explain every intricate detail.”

For Lorens, that raises the prospect of taking at least one day off during the next Braves’ season.

Think Tank: Blockchain Evolves into Geoblockchain

Blockchain technology is finding inroads in business, and its maturity curve is bending toward geoblockchain.

In a 2018 survey of global executives, Deloitte found that 65 percent of US organizations plan to invest more than $1 million in blockchain technology in 2019. For business leaders surprised by that statistic, this WhereNext Think Tank offers useful insight on this emerging technology.

Following Think Tank discussions on emerging trends in corporate security, IoT and big data, and retail, Esri’s Brian Cross sits down with blockchain expert Constantinos Papantoniou to learn:

- How blockchain technology works

- Which industries are driving the early business cases

- What a Geoblockchain is and how companies can benefit from it

Brian Cross: We’ve talked in this Think Tank series about a variety of emerging IT trends and what they mean to the business community. Today I want to discuss something called Geoblockchain. To do that, I think we need to start by explaining blockchain technology.

Constantinos Papantoniou: At its most basic level, blockchain is a new way of communicating and storing information. Instead of recording it in one place, like a traditional database does, blockchain technology records data across a distributed ledger. In the case of a private blockchain, the ledger might involve several computers run by business partners. In the case of a public blockchain, it can comprise several thousand computers.

Every transaction that occurs among those parties is validated by and recorded on each computer, or node in the blockchain. That transaction becomes a new block, and the blocks are organized chronologically to form a blockchain.

Storing data redundantly across many computers makes it more accessible and transparent to all participants, and also much harder to alter or hack.

The main advantages of Geoblockchain are speed of transactions, data accessibility, and data accuracy.

Bitcoin: Good Test Case, Bad Marketing

Cross: Business executives are likely familiar with blockchain because of its role in Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies. Can you talk about the connection?

Papantoniou: Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies have helped and hurt blockchain technology. On the one hand, crypto is a powerful test case—it has proven that distributed ledger technology works. On the other hand, it has led many people, including some business leaders, to believe that blockchain is only useful for trading speculative currency. That’s definitely not true. We’re starting to see strong use cases for blockchain in business settings.

The Business Case for Blockchain

Cross: How does blockchain improve on existing technology, and what are the business implications of a decentralized ledger?

Papantoniou: A decentralized ledger removes the middleman from the equation. That makes transactions faster and provides everyone on the blockchain one version of the truth. It’s also a purely digital technology, so it eliminates the inefficiencies and inaccuracies of paper-based transactions.

Cross: What might some of those transactions be?

Papantoniou: Blockchain can be used to record the sale of personal property—for instance, a quantity of cryptocurrency exchanged between two parties. It can also record the details of a land transfer, with two citizens exchanging the property and the assessor’s office, tax department, and public records office recording it.

In the supply chain, companies might use a distributed ledger to record and track the movement of goods. That could mean tracking where and how a shipment of fresh fruit changes hands during its journey to the supermarket.

Adding Location to the Ledger

Cross: That brings us to the idea of a Geoblockchain. How is that different from a typical blockchain?

Papantoniou: The primary technology is the same, but the data recorded on the Geoblockchain is more detailed. Companies can interrogate it more extensively and gain deeper business insight from it.

Geoblockchain is higher on the technology’s maturity curve. A simple blockchain records what happened—for instance: Property X was transferred to Owner Y from Owner Z. Further up the maturity curve, a company using a Geoblockchain might rely on IoT-based sensors and location technology to track not just what goods changed hands, but where that happened, and under what conditions.

Industries Moving First

Cross: Which industries are benefiting from blockchain and Geoblockchain?

Papantoniou: The first thing to note is that it’s still early days for this technology. But we are starting to see use cases. The financial industry has been a pioneer with cryptocurrency. Now, traditional banks are experimenting with the use of blockchain for smart contracts, online identity management, and more-efficient transfer of capital.

In the automotive sector, Porsche recently announced it is testing blockchain in its vehicles. Early apps will be built on blockchain’s ability to manage identities. That might allow the car owner to grant a delivery driver access to the car’s trunk to drop off a package while the owner is at work.

It’s also easy to imagine a next-level use case for automakers. Since many of them now offer short-term rentals to customers, they might use Geoblockchain’s identity-management capabilities to give the right customer access to the right car. Fleet managers can use Geoblockchain’s location capabilities to track the location and condition of cars.

Cross: Are other industries experimenting as well?

Papantoniou: Yes, we’ve seen early signs of Geoblockchain use in pharmaceutical and medical equipment companies; manufacturing, logistics, and retail; and healthcare. In general, Geoblockchain is attractive to companies that:

- Track the provenance of their goods

- Record transactions on paper, and

- Keep transaction data in siloed databases

The lifecycle of a traditional product shipment is tracked through many different systems by many different participants, creating many versions of the truth. Geoblockchain makes that tracking more efficient and reliable.

A Newly Digitized Supply Chain

Cross: Many companies have already begun to digitize their supply chains. Why would they need a Geoblockchain?

Papantoniou: The main advantages of Geoblockchain are speed of transactions, data accessibility, and data accuracy. Think about a typical global supply chain. A shipment of lettuce can pass through dozens of supply chain partners. Each one records each transaction, often in different systems. That means the chain of custody, even if it’s digital, often splinters into many versions of the same story.

With Geoblockchain technology, those transactions are agreed on by all relevant parties and recorded in one distributed ledger, providing proof of location (PoL) and other details. So, the companies don’t need to reconcile disparate versions of how, where, and with whom the product traveled. They can also access that data quickly because it’s on the distributed ledger, open to everyone associated with that blockchain.

A single version of the truth can be particularly valuable when, for instance, an incident of foodborne illness occurs. Then a manufacturer or retailer can quickly trace the products to their source and recall only the affected batches. That can save lives as well as time and money, and help protect a company’s reputation. Walmart, for example, is working on this now.

Cross: Where are the early use cases occurring?

Papantoniou: European and Asian companies seem to be the first-movers. Most of them immediately see the value of adding location information to the blockchain. When they combine blockchain with a geographic information system (GIS), every transaction shows up on a map, revealing the condition of the shipment, the parties involved in the transaction, and its exact location.

The Geoblockchain creates the kind of supply chain visibility that most manufacturers and logistics providers have sought for decades.

The smart city movement is also driving adoption, and places like Dubai and Seoul are investing millions to run government operations on blockchain.

Where to Begin?

Cross: How do the executives you’ve worked with evaluate Geoblockchain as a potential solution? How do they figure out where and when to pilot it?

Papantoniou: The executives we work with look at several things to make that decision. One, are there real-world or virtual items that change condition over time and need to be tracked—for example, a container of goods, a financial transaction, or a consumer product such as a car?

Number two, do those entities sometimes get mixed up or locked in different systems? If so, blockchain may help the company maintain one system that keeps a universal record of that item.

Number three, is speed of access to data important, and can it reduce time to action? Number four, does the location of the asset matter to the business? If location data can help the business make better decisions, a Geoblockchain can serve as the ledger.

Cross: If I’m a business executive who wants to explore Geoblockchain, where do I begin? This isn’t an off-the-shelf product, is it?